Redfall's Vampire Myth, the Modern Gothic, and Monstrous Capitalism | Essay

Or, When they had everything, they wanted more.

Please beware major story spoilers for the game’s main path as well as sidequests. All references will be linked below under works cited. I actually dug up a final essay for this that I wrote at uni, so shoutout to Professor Cooper.

Content warnings include descriptions and depictions of violence, child abuse, child death, medical gaslighting, and unethical medical experiments.

In Redfall, there are many things that come together to make a monster: greed, progress at any cost, and a complete loss of humanity. This manifests in a well-known gothic entity—the vampire. The game’s story charts its own evolution of the vampire myth, and the gap between what we, the players, know, and how the game constructs its myth simultaneously becomes a gap that is present in the text itself. Vampires exist in the fictional island town of Redfall, Massachusetts, but they exist on two planes: the mythological, and the scientific. Any seasoned cryptid hunter may enter Redfall only to find that well-travelled ways of dealing with the creatures aren’t going to hold water, here, holy or otherwise.

Redfall, developed by Arkane Studios in Austin and released in May, 2023, is set in the titular New England town. The sister studios Arkane Lyon and Austin, who collaborated on the Dishonored series and have since each struck out on their own, are well-known for creating self-contained environments with no way out: no way through the blockade (Dishonored), no way home to the throne (Dishonored 2), no way off the space station (Prey), no way across the ice or into the past (Deathloop). In Redfall, the sea has been turned into a wall, so the ferry’s out, and the sun… well.

Redfall harbour and shore © Arkane Studios

It all begins with the narration of a nameless young woman: she came to Redfall to help. Instead, it took everything from her.

The story of Redfall tells itself backwards, through the discovery of echoes from the past. It goes like this: four scientists wanted to discover the secret to eternal life. What they found instead, sort of by accident, was Vampirism—conveniently, that’s just about the same thing, unless someone’s got a decent shotgun and a wooden stake. Redfall can be played as one of four heroes in the base game, and it’s their task to fight their way, either alone or with the aid of friends, through the districts of Redfall and the vampire gods' territories. Each of the four vampire bosses has a backstory that the player has to come to understand before being able to confront them; not to reason with them but to obtain items necessary to unlock their lairs.

l-r: Bribon, Remi, Devinder, Layla, Jacob © Arkane Studios

At the beginning of the game, the sea is turned into a cage, the sun is eclipsed, and the player character is forced to make their way back to shore to find a way to stop the vampires. That’s the main objective of the game, complicated by several factions: the vampires and their four gods, and several human groups. These groups include both mercenaries from the mainland and resident cultists worshipping each of the four vampire overlords.

Dramatis personae

Let’s begin with a little overview of people and names you should know before going into this.

Claire and Charles Beck: twin siblings and biotech researchers. Claire is the younger sibling but Charles stands in his sister’s shadow. She’s the Elizabeth Holmes of this universe. Claire turns into the vampire god Black Sun.

Dr Peter Addison: scientist and researcher, formerly teaching at university. He turns into the vampire god Hollow Man.

Dr Alice Young: led a rehab clinic called Twintree. She turns into the vampire god Miss Whisper.

Dr Tom Kildere: neuroscientist. He turns into the vampire god Bloody Tom.

Grace: aka the Gateway. She came to Redfall to help the researchers understand her blood, which seems to have healing properties. They strapped her to a bed and never let her go, then killed her aunt to keep the secret.

Each of the gods command cultists; the fifth human faction to contend with are Bellwether Security, a paramilitary mercenary group sent to contain the situation.

The Beginning of the end

Claire and Charles Beck came to Redfall to get in touch with Dr Peter Addison. They wanted to use his research into parabiosis to conduct their own investigation into finding cures for virtually all diseases, eventually arriving at permanent rejuvenation by means of blood transfusion. Parabiosis, according to Wikipedia, is

“a laboratory technique used in physiological research, derived from the Greek word meaning ‘living beside.’ The technique involves the surgical joining of two living organisms in such a way that they develop a single, shared physiological system. Through this unique approach, researchers can study the exchange of blood, hormones, and other substances between the two organisms, allowing for the examination of a wide range of physiological phenomena and interactions. Parabiosis has been employed in various fields of study, including stem cell research, endocrinology, aging research, and immunology.” [1]

The in-universe explanation that players can find as notes scattered throughout labs runs very similar, drawing particular attention to the etymological origin, the notion of ‘living beside.’

Aevum Therapeutics: exploitation and grift

Peter Addison aka Hollow Man is the first vampire god players encounter, and his story is the mystery at the root of all the cruelty—it’s his research that’s used as the basis of what follows. Addison suffered from a degenerative neural disorder, and rather than accept his fate or attempt an ethical clinical study, he used his prestigious position at Tolland University to research his condition and conduct illegal experiments on human test subjects. After the university expelled him (but evidently chose not to press criminal charges) and the possibly subsequent divorce from his wife, Addison began to experiment on his daughter Amelia, barely ten years old at the time, in an attempt to cure himself. He regularly injected himself with her blood according to the principles of parabiosis, which eased his symptoms but exhausted her.

Due to how frequently Addison needed these “treatments,” Amelia was confined to their large house at the edge of Redfall. When she begged to be allowed to leave and see her friends, her father bribed her into acquiescence with emotional blackmail as well as (occasionally gruesome) gifts in an effort to keep her close. One of these gifts, a beautiful butterfly pendant that Addison affixed to the transfusion needle to make it all seem harmless and cute, becomes the Remnant that symbolises Addison’s guilt and the loss of his humanity. He would say, “The butterfly isn’t done yet, dear,” when he extended the treatments past Amelia’s limits. This is heavily suggestive of patterns of child abuse where adults use euphemisms to obscure the situation and to rob the child of the means to recognise that what is happening is wrong and to communicate the abuse to others. Amelia wouldn’t have had the vocabulary to describe what her father was doing in medical terms, and ‘the butterfly stings me and takes my blood’ would have probably been dismissed by any adult she might have talked to as a young child’s fantasy—not that Addison ever let anyone near her. Amelia was gradually weakened by the transfusions, and eventually died when Addison didn’t stop the treatment even though she’d been feeling faint and asking him to stop.

After her death, Addison shut himself away in his mansion, resigning himself to his disease—as far as the player knows, he attempted no other means of clinical study or treatment for his condition. When Claire and Charles Beck arrive, he’s initially resistant and refuses to hand over his research. When Claire Beck promises him a cure, however, he eventually agrees to work with them. Upon turning himself into a vampire, Addison appears utterly triumphant: there’s not an ounce of shame or remorse for the sacrifices others have had to make for him to save himself. When he realised that he’d killed his own child, Addison didn’t ask, ‘What have I done?’ in horror. He said, “What am I supposed to do now?” drowning in self-pity.

Addison’s backstory is given a lot of room in the first section of the game, as working things out includes an extended exploration of the house on separate planes of existence; reminiscent of the Dishonored 2 mission 'A Crack in the Slab.' This makes sense because the extraordinary cruelty of the tale is harrowing and sets the tone for what’s to come. (Plus, abandoned dollhouses are creepy af.)

The dollhouse in the mission House of Echoes © Arkane Studios

Claire Beck became the driving force of the scientific developments that eventually led to the discovery of Vampirism in Redfall. The medical start-up Aevum Therapeutics that she and her brother established received funding from their father and another investor—who later ended up responsible for the presence of Bellwether Security mercenaries. They weren’t sent to save anyone but for damage control: upon realising that the situation had escalated, the investor, venture capitalist Elias Kurz, hired them to take out the four people responsible to protect himself from the fallout. Charming, non?

Along the lines of the scientific assumptions underlying parabiosis, Claire Beck reasoned that the secret to curing all diseases must be found in the blood. (The blood, the blood, the blood, the blood, the blood.) Aevum Therapeutics set up clinical trials and blood drives at the local hospital, drawing in participants from across the country. Medical students like Layla Ellison, one of the four heroes, took part in clinical studies for a little extra money and extra credit. She also ended up with telekinetic powers (but doesn’t remember much of how). As time went on, Aevum became one of the world-leading companies conducting blood data research; they did also begin mass-producing pharmaceuticals. What they didn’t want anyone to know, however, was that their main source of “blood data” wasn’t the never-ending blood drives, but instead a young woman named Grace—the voice from the intro.

Grace’s story is told through collectibles scattered throughout the game, so-called grave-locks functioning like audio logs. They contain fragments of a braid of hair she gave to her aunt as a keepsake before coming to Redfall to volunteer for blood testing. Grace’s blood appeared to possess healing properties: while nearly all her family died of a mysterious illness, she (and her paternal aunt) survived. In fragmented recollection, she recalls giving blood transfusions to relatives and other people in the community where she grew up. (It’s unclear to me whether this affliction was a sort of proto-vampirism.) She came to Redfall for one reason: to help others. What happened, however, is a terrible tale of exploitation and deceit, and establishes Grace and Amelia as two innocent victims of greed and cruelty whose disappearances no-one knew to question or investigate due to the abuses of power perpetrated by those who exploited and killed them.

Aevum’s lead scientists—Addison, Claire Beck, and doctors Alice Young and Tom Kildere—quickly realised the remarkable properties of Grace’s blood, and discovered its potential for vampirism simply because it made them crave more blood, more power. Judging by Kildere’s records, it gave them visions. Hungry for more than just a few measly samples, instead of letting her go after the initial round of tests, they tricked her into undergoing anaesthesia for a procedure. She never woke again: they put her into an induced coma and from that point on only kept her alive to use her as a blood bank.

But it doesn’t stop there: upon realising the potential in Grace’s blood, they also used it to conduct illegal, undisclosed experiments on human subjects. Trouble is, those experiments didn’t take. Regardless, Aevum happily continued the trials and covered up participants' disappearances or deaths. It was then that investigative journalists started to come a-knockin' and Claire killed Charles, her own brother, to keep the secret after he spoke to one of them. (Her Remnant is the antique ornate desk clock that she used to bash in his skull, snarling the old time favourite, ‘You don’t walk away from me.’) After that, the four scientists decided to use the Gateway Sample collected from Grace (whom the Aevum founders came to refer to as the ‘Gateway’ personified), to turn themselves into vampires. Based on what you learn about them, it’s clear the procedure worked because they had already so far relinquished their humanity that it took.

As for the other two vampire gods and their personal blends of cruelty: Dr Alice Young led a so-called welfare clinic in the Northeast of Redfall—an expensive sort of spa, going by the branding and the brochures. In reality, however, Twintree Wellness and Recovery Centre was a rehab clinic where Young preyed on patients struggling with addiction and substance abuse, using them to conduct experiments surrounding the Blood Trance, a ritual to advance vampires' abilities. The symbol of her downfall—her Remnant—is the key she used to lock Grace’s aunt, concerned for her welfare, in Twintree’s basement, leaving her to starve and claw at the door.

Tom Kildere was an executive at Aevum. He had returned to Redfall to work for them, but was prevented from quite enjoying the lifestyle he had envisioned by his father’s failing health. Tired of taking care of him, Tom’s rotten soul is haunted by a memory of him walking away from his father’s sickbed, leaving him to die. Kildere’s specialty is neuroscience, and he generously experimented with psychedelics in order to try and understand the Gateway’s power. The Remnant used to unlock his psychic lair is the old-fashioned bell his father used to summon him when he needed help.

The exact science regarding the Gateway Sample isn’t explained in granular detail within the game’s lore, and it’s not the point. All we need to know for the purposes of this writing is that Claire Beck accidentally discovered Vampirism, and now it’s everybody’s problem. Redfall’s vampires live at that intersection between science, myth, and magic often explored in gothic fiction:

The set of Frankenstein’s laboratory used by Dracula in Van Helsing (2004, dir. Stephen Sommers, production design and sets by Steve Arnold) © Universal Pictures

So, regular humans become vampires through the wonders of modern chemistry. It’s not enough that kitchen drawers close automatically and that there’s 500 different kinds of plastic; no, eternal life is where it’s at. But how does it work? And what does the scientific method mean for existing vampire mythology—in the game’s world, and on the meta level?

Redfall and the vampire myth

The game’s universe has an established vampire myth (as well as many other well-known myths and urban legends); one of the heroes, Devinder, is a cryptid hunter who came to Redfall on his book tour. Trouble is, the old reliable—garlic and a polished cross—doesn’t hold. At the fire station that serves as the players’ base of operations during the first part of the game, there’s a whiteboard detailing the vampires' most prominent features (their nails and fangs) and survivability/treatment in case of an attack. The note that stands out most easily is the Bite: it doesn’t turn. If a vampire gets you behind the bins, you’re food, nothing else. “VAMPIRISM” is scratched out—signalling to the player that these vamps have surpassed the traditional myth. The information itself is perhaps not as valuable to players as it is to the characters in the story, but this diegetic awareness of the myth is an interesting factor. They’re aware of the folklore, and they’ve made observations based on those hypotheses. The vampires' takeover was so sudden, residents didn’t even have the time to string up any garlic bulbs just in case.

Crosses don’t work, holy water doesn’t work. Churches have not become sites of refuge for anyone—if anything, because they were community hubs and the clergy influential people within the community, powerful vampires can be found there. What does work, at least, is UV light: it stuns and burns the vamps and, especially when being attacked en masse, a well-aimed UV beam is what can buy the player some time, enabling them to either fight back or pick up sticks and get the hell out of there. It’s also the reason why the sun had to be, uh, switched off in favour of perpetual twilight. The day/night cycle is still perceptible, but there’s no feeling safe at any time of day. What else still works? A stake through the heart. Out of all possible elements of the folklore and literary vampire myth to tide over into Redfall, these elements are arguably the strongest because they lend themselves best to combat mechanics.

This diegetic awareness represents a recurring element in gothic fiction of knowledge, awareness, or scepticism of the myth being either a saving grace or a hindrance; in pitting rationalism against belief. One very common trope is the story of someone who believes themself above such fanciful notions, or who insists that 'there is a logical explanation for all of this,' only to be irrevocably embroiled in the supernatural. Sometimes knowing the myth helps! Sometimes it doesn't! Sometimes the existing myth is useless because the vampires don't play by the rules! It’s John Polidori’s Vampyre getting into fisticuffs with Bram Stoker’s Dracula and Richard Matheson’s I Am Legend.

In Polidori’s short story, Aubrey’s eventual understanding that vampires are real doesn’t save his sister from her fate as the magnetic Lord Ruthven’s victim. Enlightened scepticism and rejection of belief in the supernatural don’t protect Aubrey at the start, either, and then they work against him when he fruitlessly tries to warn others of the danger. In Dracula, Mina Harker becomes Van Helsing’s meticulous chronicler and knowledge expert. Still, even as her notes and research prove to be integral to the vampire’s defeat, she is patronised at every turn. In the end, her faithful account becomes nothing more than a fanciful record she’s being gaslit into believing sprang from her fantasy (especially where it concerns Dracula as the symbol of repressed, not merely sexual desires); they are ill-suited to securing her a future as a journalist despite what she’s experienced. In I Am Legend, there’s a circular influence: the protagonist wonders, do the infected behave like vampires because this is what vampirism is, and its record in folklore is based on an earlier outbreak? Or did awareness of the myth make the infected develop these symptoms; do they act as they believe they should? And could that be the key to either defeating or curing them?

Or, of course, you could watch the Disney Channel Original Movie, Mom’s Got a Date with a Vampire, get yourself a continental gentleman.

Caroline Rhea and Charles Shaughnessy in Mom’s Got a Date with a Vampire (2000, dir. Steve Boyum) © Disney

(Psst: it’s the kids’ knowledge of the vampire myth and ways of defeating them that saves the day, even though in their world the existence of vampires is officially relegated to fiction, superstition, and Van Helsing’s work to pseudoscience. He abandoned his thriving New York city practice, don’t you know.)

But why doesn’t the Bite work?

Redfall and the modern gothic

Socio-economic dynamics expressed in Redfall’s vamps

Returning to my earlier point about experiments to make innocents into vampires failing, but Beck, Addison, Kildere and Young turning just fine because they’d already compromised their humanity, possibly their souls. This is reflected in how more vampires are created: victims aren’t being snatched off the streets to be turned, only to become feeding sources. In order to become a vampire, a person has to volunteer and undergo the experiment. The benefits are clear: living forever, feeding on their innocent former neighbours they didn’t like, controlling as many as possible below them in the new order. If someone wants all that, they have either already lost their humanity, or are demonstrably willing to relinquish it. The same applies to the gods' cults: to join, prospective members have to bring a sacrifice. There are stories about parents sedating and surrendering their children in order to be granted a place among the cultists. One of your own companions from District 1, Joe, sells out his wife and unborn child in order to secure his own future. If you can’t fight 'em, join 'em. The gist here is that people choosing to join these ranks were already monsters before they physically turned into them. The four leaders didn’t become “gods” because they were larger than life somehow. They became gods because that’s what they already saw themselves as.

The cruelty is the point, and there’s enough of that in them already.

Abuses of power, greed, and exploitation of unjust systems are recurring features in Arkane Studios games. After industrialist exploitation in Dishonored and biotech overreach coupled with dehumanisation of the self in Prey, it’s hardly surprising to find literal vampires next in line.

Redfall is an island town, a close-knit community. Notes and other documents that make up the main part of the game’s tangible lore reveal that social stratification was what one might expect of a New England town like this: very likely predominantly white, with a few families that probably came over on the Mayflower laying claim to its foundation. There is, somewhat predictably, a note found by a dead man, written in his own hand and declaring, “Do these people know who I am? My family owns this town!” Redfall’s economic situation is not explored in detail, but we can make a few assumptions based on its past in the whaling trade, which very likely rather abruptly gave way to alternative power sources. There’s a sense of holding onto the past and putting it on display, but the lighthouse museum showcasing old whaling equipment and exploring the lives of seafarers is small and, by the start of the game, in a state of disrepair. The main economic motor of Redfall, aside from Aevum Therapeutics, appears to be its shipyard, its continued fishing trade, and tourism by way of the ferry from the mainland.

The community’s social and economic stratification is mirrored within the vampires' and cultists' hierarchies. Status in life determines one’s status in eternal life, none too rarely with tragic consequences. People with wealth and status are more likely to become more powerful vampires—as indeed they are more likely to want to be vampires in the first place, craving to extend their reach and control over others. The disenfranchised and marginalised of Redfall are far more likely to end up as Bloodbags (specialised food sources), either because they were betrayed by others or because they saw no other way to survive but to join the cultists. Those who wanted to join, who sold out friends, family, and neighbours willingly, thought of survival as a nice way of getting ahead. Churches are situated near the centre of each district neighbourhood and more than one of the heroes' targets is found in one; at least one of them was, indeed, a pastor.

The pastor-turned-vampire is part of a side mission for Connie, one of the survivor NPCs, but one of the Underbosses you have to defeat to secure an entire neighbourhood has taken up residence in a church and is, in fact, called Gideon. The second, named The Bride, also controls the neighbourhood from within a church. Christian churches do not serve as sanctuaries; it makes sense for powerful vampires to make them their hunting ground as humans may still be drawn there to seek refuge. However, it’s also an indication of those vampires having had high social standing within a congregation, whether they used to be clergy or not, thus either extending that power or perverting it for their own ends. It’s no coincidence that Reverend Eva Crescente, the leader of the group of survivors based out of the fire station, hasn’t been able to make her church a safe haven. Along with the distinctly WASP-ish (short for White Anglo-Saxon Protestant) appearance of the island’s remaining upper crust, this places the church in one of the upper strata, aligning it with the vampires' symbolism of greed and predatory behaviour.

When metaphorical bloodsuckers turn into literal ones, hierarchy is an important aspect—both in terms of the emergent power structure and the high value of social mobility. All beings that throw their lot in with the four gods know only one direction: up. Regular vampires dream of moving up in the world via the Blood Trance, cultists want to be as close as possible to the gods they worship; they want to become special one way or another. Here, cultists ride that edge between exploiting and exploited—they exert abuse and hazing within the ranks, they express contempt for those who refuse to come willingly, but those who become Bloodbags are also no more than a cheap source of blood. Still, they hiss and spit about their own importance even as they’re furthest down the food chain, literally.

Elements of Othering—regarding the vampire as the subject of xenophobia or socioeconomic anxieties—are largely absent in Redfall. There’s no great emphasis placed on the residents' response to Aevum establishing themselves in the town; there’s no trail of lore characterising them as interlopers or outsiders.

The capitalist vampire in traditional and modern gothic fiction

The parasitic nature of the vampire as a bloodsucker in the metaphysical and very much the plainly physical has been a theme since the emergence of the literary vampire. Vampires have been preying on lower-class victims who wouldn’t be missed since the 19th century, as a metaphor for the aristocracy and industrialists exploiting the working class. The noble, aristocratic vampire stepped on the scene with the enigmatic and dangerously charismatic Lord Ruthven who moves through the upper echelons of Europe with ease. Count Dracula hires our dear friend Jonathan Harker in order to acquire a home in England, so that he may establish himself there. All he needs to accomplish the venture is massive wealth and social graces (much as the bourgeoisie of England is afraid of him and the impending upset to the economic power structure), and before you know it, an anaemic solicitor from London is trying to cross the Carpathian mountains in his socks, fleeing from his own mirror image.

In Zombies, Spectres, and a ‘Great Vampire Squid’: Monstrous Capitalism and Financial Fear in American Gothic Fiction, Amy E. Bride argues that Anne Rice’s Interview With A Vampire, which turned the myth toward the suffering, haunted, wretchedly human vampire, symbolises the predatory and exploitative effects of economic deregulation under the Nixon and Reagan administrations (Bride 2019, p. 139ff). In Monsters of the Market: Zombies, Vampires and Global Capitalism, David McNally suggests that fictional monsters symbolise our fear of the market in order to avoid ‘naming capitalism as a monstrous system’ (p.3).

In Redfall, the final transformation of the four scientists into vampire gods is, essentially, overextended damage control. After a disastrous interview during which Charles Beck failed to obscure his own qualms with his sister’s work and promises—and the journalist nailed him pretty good on whether Aevum had been misrepresenting the purposes and the progress of that research—investor Kurz tells Claire to ‘fix the problem.’ That problem is Charles' scruples and the resulting threat to their bottom line. It’s implied that Aevum’s PR strategy up to that point had been not to comment on ‘legal disputes with former staff […] alleging fraud.’ After that interview, using the Gateway to turn themselves into vampires is Claire’s grand plan to maintain control, by any means necessary. Faced with her brother’s concerns, faced with regulation, this is her response: “You want to know how I feel? Alive. More than alive. Like I could anything I wanted and no one could stop me.”

Exercising their exploitation of others is what makes these people feel alive. It elevates their experience to where they think they belong: above everyone else, above the rules, above the law.

In vampire stories of the 21st century, vampires have surfaced as symbols of gentrification, for instance in Vampires vs the Bronx, a 2020 horror comedy directed by Osmany Rodriguez. Three teens, Miguel, Luis, and Bobby, have grown up in the New York Bronx and, young as they are, are able to track the changes that their neighbourhood is going through. Gentrification does as it will: rich people buy people out of their homes, move in, the neighbourhood is sanitised and quote-unquote improved, and so the entire atmosphere changes. When residents go missing, the boys eventually realise that this is the work of vampires. The adults don’t believe them, so they have to go hunting themselves.

In Redfall, too, people have been going missing for a while. These disappearances are systematically covered up by Aevum, but to hear Layla tell it, living in Redfall was starting to feel oppressive, the idyllic small town veneer crumbling even before neighbours grassed each other up to save their own hides. The game then ties all of these threads together and points to white privilege, capitalism, and deregulation as the source of the monstrous that is plaguing Redfall. Making subtext, text, as it were.

Everyone’s hot and no-one is horny

Subtext that’s missing, however, is the bit where everyone’s horny for the vamps. Redfall doesn’t get in on the monsterfucking, full stop. Now, don’t get me wrong, especially the special vampires are designed to show skin. The trouble is, there’s no-one around to be horny about it. Players may think, ‘Step on me,’ but the text doesn’t have sex appeal built in. To illustrate the point with an extreme example, think of Lady Dimitrescu in Resident Evil Village: she’s sultry and unbelievably hot, rendering players the world over beside themselves with lust, and she briefly puts up a seductive façade with protagonist Ethan Winters, as do her “daughters,” but the game itself is desperately un-horny. Nothin', zip, zilch, no matter how respectfully I’m looking at Chris Redfield’s enormous biceps. It’s not for nothing that Capcom were surprised at Tall Vampire Lady’s lightspeed rise to fame. You wanna know what’s horny? Bloodborne. In the best, grossest possible way. [2]

The point isn’t whether players find the designs sexy or whether horniness can be injected into the text by way of fanworks because all of that is entirely subjective. The point of this is to examine the in-universe level of horny, and there’s none. None of the four heroes ever meaningfully comment on the vampires' appearances, none of the NPCs do; there’s no lore in the form of notes to even mention that some of them look hot. The cultists dream of becoming part of the Blood Trance, which conceptually has potential as a metaphor for sexual congress, but here’s the biggest clue: no matter what’s going on, no-one is moaning. No groaning, grunting, gasps for breath. Only slurping that you can hear from several blocks away. (This is not a knock, the sound design is great, amplifying contextual sounds depending on the level of danger you’re in.)

The eroticism of the literary vampire starts with feeding: in itself an act of penetration, feeding becomes symbolic of intercourse. Dracula comes to Lucy and Mina at night not have sex with them—or does he? He feeds on them, exerting over them a thrall that calls to their desires. Lucy Westenra steps over the threshold entirely, finding in her vampiric self actualisation of the desires spurned in young ladies of her rank: a want of sexual independence, but also freedom from the constraints society places on her. Mina Harker, on the other hand, feels the same draw toward Dracula but ends up successfully contained by the men in her life: her husband, Van Helsing, Holmwood et al. There’s a fantastic reading in Vampiric Affinities: Mina Harker and the Paradox of Femininity in Bram Stoker’s Dracula, of Mina’s continued desire for Dracula and what he represents both physically and in terms of her want of socioeconomic freedom, even after he’s been vanquished.

From Roger Ebert’s review of the 1994 film adaptation Interview With The Vampire:

The initial meeting between Louis and Lestat takes the form of a seduction; the vampire seems to be courting the younger man, and there is a strong element of homoeroticism in the way the neck is bared and the blood is engorged. Parallels between vampirism and sex, both gay and straight, are always there in all of Rice's novels; the good news is that you can indulge your lusts night after night, but the bad news is that if you stop, you die. [3]

In Redfall, the vampires don’t seem to feel pleasure during feeding beyond slaking their hunger. They do comment on enjoying the hunt and liking it when the humans they pursue feel fear, but the text takes care not to let that tip over into something psychosexual. In keeping with the characterisation of Redfall’s vampires as capitalist predators, the kick that the vampires get from this is limited to predation, control, and exploitation in the sense of… assets. Human resources, if you will. If the vampire gods thirst for anything, it’s for power, but their relationship with the outside world is perfunctory as they’ve hidden themselves away in their psychic spaces. This echoes the notion that, in order to become vampires, they first had to give up their humanity. Earthly pleasures are of no more consequence to them. Since the Bite doesn’t turn, there’s no sense of sire/siree relationships, no possessiveness, no ownership of the individual; only abstract power and control over people and territory.

Lestat, right now: Couldn’t be me.

Speaking of that guy—queerness and the gothic are inseparable: we fall in love with the monsters because it promises us that we, too, are worthy of love. Othered by society at large and our own families and communities, queer people have been well familiar with being likened to monsters themselves. Carmilla is a lesbian, Louis and Lestat are so very, very gay, and queer readings of Dracula have stood the test of time—along with a very intense letter Bram Stoker once wrote to Walt Whitman. That sense of Othering isn’t a part of their characterisation here.

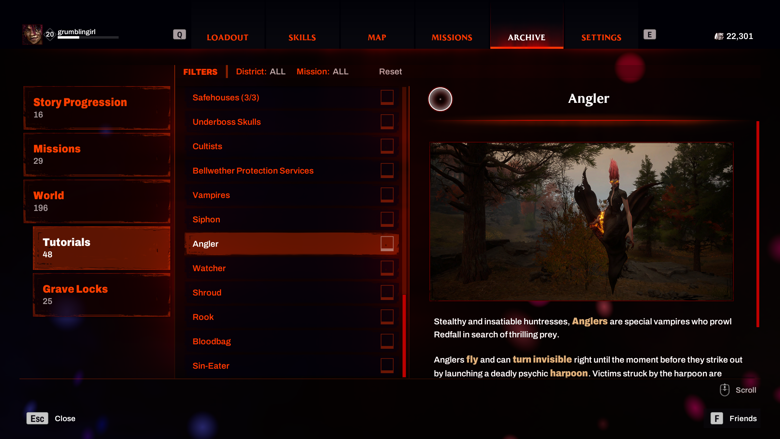

What stands out a little in all this, however, is that the female-coded vampires (the Angler and the Shroud) have character descriptions lightly evoking the monstrous feminine and elements of cruel beauty, while the male-coded special vampires (Siphons and the Rook) are slab-chested hunks with open cloaks that show off their abs. Their descriptions focus solely on what they can do in terms of game and combat mechanics. The descriptions for the Angler and the Shroud contain that information, too, but there is explicit mention of their allure and they’re viewed through a lens of frightening sensual appeal, calling them insatiable huntresses who play with their food and emphasising their looks and “cruel embrace.” This is just two pages in the in-game lore, though, so it’s not much to go on and it’s not borne out in the gameplay. The only visible flourish is the Angler throwing her head back in something resembling rapture after getting a good bite out of you.

In-game Archive > Tutorials > Angler © Arkane Studios

Captain Oikonomou after reeling Layla in © Arkane Studios

No time for eternal suffering

The literary vampire has undergone many shifts and transformations: among them the journey from a mythical, otherworldly creature to be banished with a whole bag of tricks, to a being that is as wretchedly human as the rest of us, if not more so. Eternal life brings grief and shame to Louis de Point du Lac, at the same time as Lestat makes the most out of a situation that he reveals only at the end he had no choice to enter. The vampire became demythologised as the protagonists' view shifted from those trying to use whatever knowledge available to defeat the villain, to the vampires themselves [4]. We see, now, all those horrendous acts through their eyes, and part and parcel with that come all those tropes and feelings: self-loathing, guilt, horror at what they’ve become.

The vampires of Redfall haven't been around for long—and it’s consistent with their want of control and power that they were after eternal life in the first place. When they die, they don’t lament that perhaps their time has come; it’s not been long enough for this to have turned sour for them, of any rank. Had the game been set further in the future, this might have become part of the story. As it is, when you stake them, they cry out, “No, not me!” because they believed themselves invincible, too special to fall now. They felt like they could do whatever they wanted, and no-one could stop them. And when you come along to stake them, they cry foul.

Conclusion

Redfall’s vampires' existence hinges on exploitation, greed, and loss of humanity. They’re the ultimate monsters of monstrous capitalism, deregulated finance, and medical research. People, to them, are expendable; a food source at worst, willing soldiers and pawns at best. The vampire gods taking control has enabled both the vampires and the cultists to indulge in their worst violent impulses.

An... experimental tableau at Bloody Tom's cultists' base © Arkane Studios

The game deliberately subverts some familiar tropes while making others part of combat mechanics, and it slots right into the long-standing relationship between vampires and monstrous capitalism. It eschews eroticism and queerness as subtext as well as the brooding literary vampire struggling with eternal life. Where the modern literary vampire is so devastatingly human, the vampires of Redfall abdicate their humanity to achieve what they really, truly want: absolute control and carte blanche.

Works Cited

[2] Visceral Femininity: A Bloodborne Video Essay. Honey Bat, youtube.com

[3] Roger Ebert's review of Interview with the Vampire (via Web Archive, retrieved 02/09/2023)

[4] Thesis title: The literary vampire – From supernatural monster to the actual human? Marianne Kristensen, University of Stavanger, 2010.

Zombies, Spectres, and a ‘Great Vampire Squid’: Monstrous Capitalism and Financial Fear in American Gothic Fiction. Amy E. Bride, University of Manchester, 2009.

Monsters of the Market: Zombies, Vampires and Global Capitalism. David McNally, Haymarket Books, 2012.