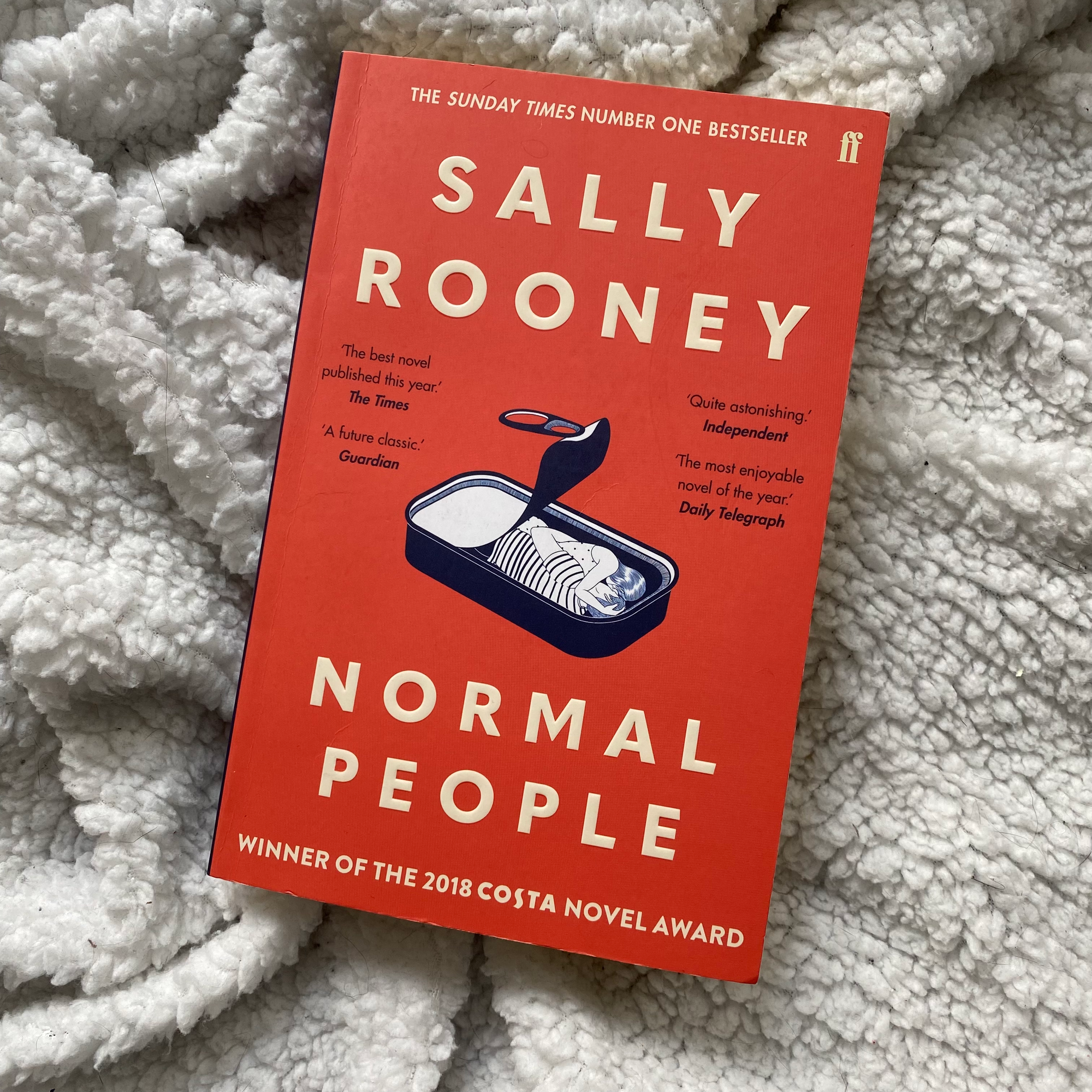

Normal People — Sally Rooney | Review

Spoiler warning! This review contains major, in-depth spoilers for the novel both in terms of plot and emotional beats.

Content warnings: the novel contains depictions of domestic violence, emotional abuse, and mentions of childhood abuse.

In Sally Rooney’s second novel Normal People, people make decisions based on what other people may think of them. Often, they make those decisions in spite of what they make them think about themselves.

The Illusion of Being Uncool

At school, it’s the illusion of being perceived as uncool that drives them to keep their relationship a secret — until, years later, it turns out that pretty much everybody knew and no-one cared. Marianne keeps the secret because she thinks Connell wants her to. Connell keeps the secret because he thinks people will think he’s a loser, going out with the girl no-one talks to and who always reads books at lunch. Plus, Connell’s mum works as a cleaner for Marianne’s wealthy family, so there’s also a social gulf between them. At school, Connell is popular: he’s on the football team, he’s got stellar grades. He’s the elusive nerd jock. His friends are jerks — sexist, horrible roosters who talk about girls like they’re meat. Connell doesn’t call them on it, until Marianne ends up being sexually assaulted at a party.

But then they graduate from school, Connell and Marianne break up because he didn’t even think to ask her to the dance, all to protect his reputation. They both end up at Trinity in Dublin, and that’s when things turn around. Here, it becomes clear that her family’s wealth is a key that opens doors to Marianne that remain closed to Connell — until they run into each other, and she pulls him into her circle of friends.

Marianne got hot, is the long and short of it, and she’s got friends, now; while Connell is the one who feels like an outsider. Not least because he realises that at a prestigious college like Trinity, studying literature isn’t a pursuit, it’s a lifestyle. People come to class to talk about books they haven’t read, and they have those books on their shelves only because they’re the right titles to make them seem cultured. Connell, with his true love for writing, realises that it’s all a sham. He tries to find friends who are likeminded — meanwhile, Marianne has friends who can afford not to care about politics. She has boyfriends who act like jerks — classist, sexist, racist. Even though we know how opinionated she can be, Marianne doesn’t call them on it, because she is too afraid of alienating her entire social circle.

That is, until they end up dating again.

It’s the happiest time of Connell’s life.

And then, he ruins it.

Cruelty and Miscommunication

The story is characterised by people being cruel to each other, and to themselves. Connell is cruel to Marianne when he keeps her his dirty little secret at school. He doesn’t understand that it might hurt her when he tells her that he’ll be moving home again over the semester break because he can’t afford to stay in Dublin, and that he assumes she’ll be wanting to see other people if he’s gone for three months, instead of telling her he’d like to stay with her.

Marianne lets him keep her his dirty little secret because her self-esteem is so ground down and damaged by her family’s emotional abuse, by her late father’s physical abuse that her brother now continues on. She feels as though she only deserves to be used.

And one day, after she’s confided in Connell about her trauma, he finds himself thinking, “I could hit her now and she’d let me.” It shocks Connell to the core that he’d think that, that he might want to; but as is the nature of intrusive thoughts, they do not represent the worst of us. This is the second time a death knell chimes for their relationship.

The thing is: Connell is right. Marianne’s cruelty towards herself is her own.

She craves relationships with skewed power dynamics. She craves submission, to be dominated. The fact that this is presented as the result of being physically and emotionally abused may turn some readers away from this story, while others may recognise themselves in it. The connection made is perhaps a well-travelled one, but the fact is that reality bears it out. It becomes clear that Marianne seeks to submit to people, but finds those who are only interested in her submission, not in caring for her. Marianne seeks these relationships in order to regain her agency, and in order to exert that agency over what happens to her. She thinks that if she wants these men to hurt her, it means she’s in control.

But it turns out she’s not, and each of these experiments fail.

Connell fairly rescues her from her boyfriend Jamie, who has a choleric temper. They’re together again, and Marianne asks Connell to hurt her during sex. He says he can’t do that. It makes him feel sick, which makes Marianne feel sicker.

A Happy Ending?

In the end, they’re together again, and they’ve found a relationship that gives Marianne that agency: Connell works to let her submit to him, to explore that part of herself, without hurting her. He turns that agency over to her. The only doubt that lingers with Marianne is whether he loves her.

He’s never said it.

Connell gets an offer from an MFA program in New York that he never thought he’d get. He says he won’t go without her. She says he should. He says he loves her.

Another chapter of their relationship closes, but this time it ends with Marianne being hopeful that they’ll see each other again. She can cope with loneliness, because she’s finally rid herself of that pain that lived inside her.