Dishonored’s Flooded District: Crumbling Bonds and the Trials of Revenge | Essay

Or, why this mission is my favourite

If you'd rather watch this as a video, then I've got you covered:

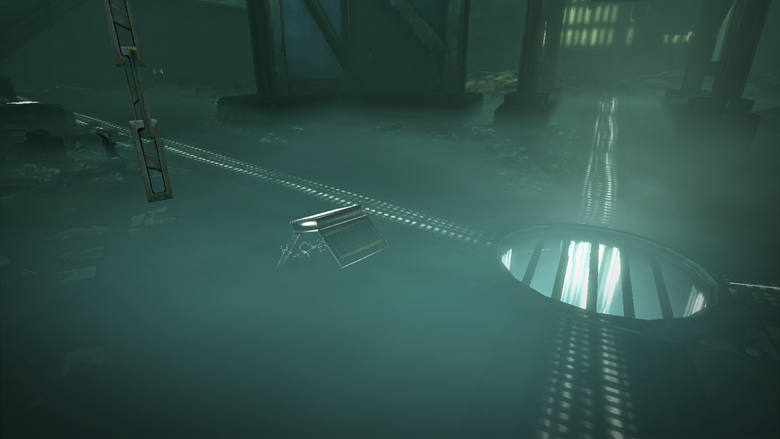

Every now and again I get asked what’s my favourite Dishonored mission, and every time I come back to the Flooded District. I love the atmosphere, I love the soundscapes, I love the way that on the surface there’s very little going on, while things are boiling just underneath.

Dishonored being a stealth game, you can play the entire thing without anything really happening aside from you choking someone unconscious every now and again. It’s quite tranquil, actually — at least so long as you don’t get spotted. Because tranquility’s all well and good, but in Dunwall everything is never more than a shattered whiskey bottle away from breaking out in chaos.

But the story isn’t only in what you do: it’s in everything you see. It’s the despair in the environmental storytelling; it’s the way it’s constructed and the role it plays in the narrative itself. For all of that it’s my favourite.

A big part of that is you’re going up against other heretics, finally. Up until now, you were generally the biggest threat in any room; but here you are, surrounded by several dozen master-trained assassins who are not only ready to be incredibly mean to you, but they can teleport as well. For the first time, you are truly outnumbered and your magic is not guaranteed to give you an edge.

Another red thread that pulls itself through the game is obviously the element of masking, hiding Corvo’s identity, committing more or less honourable deeds while hiding your face. There’s three levels in the game where masks play a very prominent role. That’s the High Overseer Campbell mission, the Boyle masquerade, and the Flooded District level. I’m going to talk for a bit about those first two missions before getting back round to the Flooded District.

At Holger Square, Corvo’s literally fresh off the boat, he just got sprung out of prison and has been sent out on his first assassination mission. In the Void, during a serious cheese dream, the Outsider chucked Blink and Dark Vision at Corvo and said, ‘Go and crack a few skulls, have fun.’

As a player, you have approximately no idea what you’re doing, and you get sent into Holger Square, which is chock full with Overseers armed to the teeth, well-trained, who will take your head off without hesitation. And they’re all wearing these incredibly grotesque masks, all of them identical. When you first play it, you feel — I still feel, after dozens of hours in that level and several replays — menaced.

One of the genius things is the level design of that place. Of course once you’ve found a route that takes you past everyone and you don’t even have to knock anyone out to complete the mission objective, you’re golden, but when you first play it, you get thrown into that building, you’ve got these long and winding corridors, and it all folds in on itself, lots of doors going off into a dozen rooms. You have no idea what’s behind them; Dark Vision isn’t upgraded yet, so you can barely see through the next two solid walls. So you’re in these corridors, and sometimes six or seven yellow silhouettes pop up and you’re like, “Oh good. That’s how it’s gonna be.”

That’s what I love about Holger Square, because even if you are staying out of sight and even if you don’t go near anyone, you still have to look at them because you have to figure out how to get past them. You simply have to acknowledge their presence in order to achieve your objective. And you have to look at those ding-dang masks, a lot! You have to overhear their conversations for hints. You don’t know what you’re doing, and even if you’re lucky on the first go and you stay out of trouble, it still feels like a mousetrap.

The corridors are narrow, tight, and there’s unnecessarily many blind corners, and you’re just grateful for the lamps and any tall shelves that you can perch on and watch for a bit. The floor is lava. Holger Square teaches the player how to find the stealthy routes by paying attention to the environment and the verticality. But occasionally, you have to get on the ground. Slap bang in the middle of I don’t know how many Overseers who all look the same; so you can’t even be sure whether the one that just passed you underfoot is the same one you saw three rooms down, or whether it’s someone new.

About masks and the Abbey of the Everyman: they’re a faceless righteous army. They have no need for a face, meaning no need of individual identity. In fact, they are forced to leave behind their entire lives upon induction into the Order. And so, because they serve the Order, their function in society, their purpose, is their identity. Who they are under the mask doesn’t matter, not to the Abbey itself, nor to the people of Dunwall. The Abbey has one face, and all who serve it wear that face.

And that’s how Holger Square teaches you how to cut through the crap to get to your target, but also how to observe and learn which of these masked dudes is which. To be methodical, and pay attention.

Then you get to the Boyle party where there’s also masks everywhere and every turn you take is a left because it gets weirder and weirder by the person you’re looking at; by then you’ve got rid of Campbell, you’ve got Emily back, you’ve kidnapped Sokolov and stuck him in a cage. You know what you’re doing, you’ve upgraded your powers unless you’re running it Flesh and Steel, you know how everything works, you’re halfway through the game; and if you’ve got Bunting’s invitation, you stroll on into that party and absolutely no-one is the wiser.

So you sign the guestbook and you’re just standing there, hands on your hips, going, I’m not scared of any of you. How about that? You’re not scared of the guests, nor of the couple of guards, please. The party has this element of social stealth to it. Usually, wherever you go, even when others are masked, your mask stands out, Corvo’s mask stands out. It puts a target on his back. At the Boyle party, masking is for fun and as horrible as your mask is, it doesn’t stand out. Some of the guests even make lusty comments about Corvo’s mask being the same as the one on the wanted posters, well done! They think it’s a lark! They think some rich guy had it commissioned for shits and giggles. It’s bad taste and judgment and they think it’s funny!

The Boyle sisters, having a guessing game going which one of them is which underneath identical masks and dresses, are also taking advantage of their own social stealth.

So you’ve got freedom to move among the guests and even your targets, but also the awareness that they don’t know that they’re the sheep and you’re the wolf. They have no idea how dangerous this masked stranger is. And even when you’re playing Low Chaos and leave them all alone and then do something absolutely despicable to one of the Boyle sisters; even then you’ve got this thrill of “You have no idea what I could do to you.”

Everyone wearing masks and acting above the law also evokes the time of Fugue. That time literally between one year and the next during which everything is permitted. Masking everyone means encouraging gossip and falsehoods. Everyone hates each other and will happily stab each other in the back with a smile; anonymity means impunity — which these people enjoy anyway, but they will use any excuse to drive it to excess. Even having this party in the middle of a plague, while the rest of the city is under strict quarantine, people are dying by the hundreds every day... well, that rings a bell, doesn’t it.

Everywhere else, you walk in and you’re immediately in trouble, but here you can move freely so long as you don’t stab anyone. Stealing is fine! The other guests encourage you openly. It’s almost relaxing. And then, you come out of the party and you’ve got the Master Key to Dunwall Tower, and your next target is Lord Regent Burrows. And you do that, too, and it feels like the game might end there — but it’s not over yet!

It turns out that you were betrayed, again, you’ve been poisoned and dumped in the Flooded District. You’re finally face to face with Daud again, the murderer of the Empress, but you’re in no fit state to fight him. Your gear gets taken away and you’re up against a dirty dozen of assassins: again masked, all anonymous. And they have magic, same as you.

The Whalers are a faceless shadow army, with clear hierarchy represented by their clothing, but concealing their faces for the obvious reason of evading the City Watch and Overseers and because their identities, too, don’t matter. It’s unknown whether the Whalers ever take off their masks amongst each other or in front of Daud (in the games, only Billie ever removes hers when revealing her betrayal of Daud and thus symbolically shedding her allegiance).

Daud uses their real names, the Whalers have no codenames, so internally, their identities do matter; in contrast to the Overseers who mostly call each other “Brother.” But to the targets they’re sent to kill, it won’t make a difference whether Rinaldo, Rulfio, Galia, Montgomery, Jenkins, Misha, or Kieran are coming to end their lives. Just perhaps if Daud takes the contract and carries it out personally — but he is the only one who never wears a mask. Targets may know that, too.

That’s the glorious bit about the Flooded District and turning the narrative around on you: masks and magic, here, are the great equaliser. Yeah, we can all do magic, you’re not special. So far, Corvo relied on his new abilities to get him where he needed to go (let’s leave aside for a moment the fact that you can complete the game without making use of them). And now, suddenly, you’re up against trained assassins who’ve all had their magic for a lot longer than you. The Flooded District mission completely turns it around on you, and it’s in the same vein that Holger Square was up to teach you the rules, the Flooded District is there to test you. It strips you of your gear, it pits you against other magic users, and it puts you into a, from verticality to sprawling to the buildings to the structures, architecturally incredibly diverse and interesting level map. You’ve got water, you’ve got run-down factory buildings, you’ve got tall office buildings and apartments all interconnected.

In Rudshore, the dead and dying are disposed of to safeguard the city — without dignity, without care. Their disposal is as much about quarantine as it is about not inconveniencing the rich citizens with all this suffering. Corvo was left for dead (albeit in this act, Samuel saved him) and cast into that hopeless area from which no-one else has ever escaped. The Loyalists knew they were nothing without Corvo as their assassin, but now that he’s achieved their aims, he’s expendable. They underestimated him, of course, but that is what his arrival in the district means. No other district in the city has had such a disastrous fall from grace.

It is telling, then, that this is where the Whalers live. They can come and go as they please, unless Daud takes the sewer key hostage. Everyone else is trapped, in perpetuity. It’s really far removed from the city proper, it almost feels like an enclave in its despair.

Without your resources, you need to make the most of the abilities you have and the opportunities that the environment affords you. It makes you manage your power use because, while Blink and Dark Vision let your mana recharge, the window of opportunity getting past the Whalers guarding your “cell” is super tight. You could also possess a hagfish and swim out, but what if you don’t have Possession? And if you do, remember that the mana drain on that is huge, and you collect exactly one vial in there. You have to be fast and you have to be aware of the cost of your abilities. Once you have a shot, you have to move.

Obviously once you get to the refinery and you get your gear back, you’re in better stead, but once you get into Rudshore, any wrong move will put you at the tip of at least a dozen blades. And then you trundle into Daud’s quarters and it’s difficult to get at him without triggering the fight. If you do fight him, then you have to decide whether to let him live or not, providing you that narrative closure — if that’s what you want for Corvo, because you don’t have to interact with Daud at all. You can add insult to injury and never even touch him.

This is why the Flooded District is my favourite mission and level: both for how it feels to play it, the environment and the storytelling, but also the place it holds in the narrative; what it teaches the player, and how it resonates with the themes and motifs of the story. It’s about uncovering more information about Daud and the Whalers, and a confrontation that’s been a long time coming. It’s a turning point for Corvo, it provides closure, one way or another, and it’s a test of the player’s abilities.

You get closer to Daud’s hideout, and there’s Overseers dead and dying. One masked faction invaded the other, and the Overseers lost. They were your first test, and here now is your second. The Flooded District is also one of two locations that we see both from Corvo’s perspective and from Daud’s. Both of them find things connected to the other, and they look at things through such a different lens. Their different abilities mean that the places they’re in warp and bend around them even though they’re mostly the same, structurally. There’s a line connecting their choices and the things that happen to them.

Daud’s lethal/non-lethal choice is also the one with the least emphasis on poetic justice and revenge. You either kill him or you don’t, but there’s no elaborate scheme to dispense punishment that won’t kill him. This is the turning point of the game, because this very simple binary choice continues for the following missions. The idea of revenge for Jessamine’s death ended with Burrows: from there on out, it’s about revenge for Corvo. And for Corvo, it’s much less political and far more pragmatic. These decisions don’t involve other people and their judgment, only his.

Obviously now when I replay this mission, I lovingly choke out all the Whalers, I put them in their beds, put a glass of water and an Aspirin on their bedside table, and then I go and have a chat with their Da(u)d. That’s because at this point, they’re my little stabby magic children. But when you first play it, all you have is nothing in your pockets, a mask, and a couple of bricks. You’re meant to be scared. You can walk in there cocky as anything, but it might just go wrong.

But if you do make your way out of there, past a bunch of well-trained assassins and their hard-boiled egg of a leader, and then out of Rudshore; deal with Granny Rags if you fancy nearly drowning; back to the Hound Pits Pub and there’s guards and tallboys absolutely everywhere, but ideally after all that, you’re not scared of them, either. Besides, the game gives you a big red button to put them all to sleep, conveniently. This bit is supposed to go quick, after having an absolutely harrowing time. You passed the test. And at this point, really only your Chaos rating cares whether you turn them all into crispy bacon.

Now, let’s come back to the mask. You don’t stand out at the Boyle Mansion, whereas everywhere else it marks you as the threat. Functionally, that’s where Kingsparrow Island is very interesting, because everyone knows who’s coming, and they know exactly who’s under that mask. But Corvo still wears it, and I believe not just for the lenses. He keeps it on when speaking to Havelock in Low Chaos and to the others in High Chaos. Before, the only people who knew him without his mask were the Loyalists at the Hound Pits Pub: because they were not a threat. While out in the city, perhaps the mask gave Corvo a way of separating himself from his actions as the Royal Protector turned Masked Felon.

But when he comes back from the Flooded District, he doesn’t take the mask off, either, because he’s uncertain who he can trust. The pub is not a sanctuary anymore. Everyone’s potentially a threat, at that moment. At the very least, everyone is now a part of the mission. In going to Kingsparrow Island, his former allies have now become his targets — their masks came off.

Of course they never wore any, they were never marked as threats. So now, Corvo’s intention is certainly to be menacing: he won’t let them face him as he was, as someone familiar, as their pawn. He’s facing them as the Masked Felon (or Assassin). The Loyalists did promise him he’d get to go after the true assassin after removing Burrows from the Regent’s Office, but they never had any intention of making Daud a target. They never cared. And now, they themselves are the targets.

In the Overseer Campbell mission, the mask is new, it’s grotesque, it’s necessary. it serves a purpose. At the Boyle masquerade, it’s an asset as well as a mockery of the other attendees. At the Flooded District, it’s to protect himself, taking the role others pushed on him and making it his own. At Kingsparrow, he wears it to make a point.

All of this hinges on the Flooded District being the turning point of the game: for the story, for Corvo, and for the players. That’s why it’s my favourite Dishonored level.