Convenience Store Woman — Sayaka Murata | Reading journal

I am very much enjoying this — quite short — novel, as bewildering as it often is.

Bewildering mainly because on the one hand (and I’ve seen people bring this up in reviews on goodreads) … nothing much happens; certainly for the first half of the story.

As for nothing happening: I love narratives like this, where on the surface nothing much happens, and that is just a window into the protagonist's life. The undercurrent of absurdity — and what could, as a concept, even push this story into the horror genre, which is quite a leap from absurd comedy, but the two lie startlingly close together a lot of the time — is Keiko’s deadpan delivery of her… let’s call it unique approaches to problem-solving. Like, yes, you can pants your teacher to shut everyone up. Or… other things.

I love that Keiko is utterly nonchalant about, at times, horrifying considerations. And yet, we all recognise them: intrusive thoughts. It’s hilarious that the things about her that may actually need ‘fixing,’ go so wonderfully ignored (past looking to blame her family and assuming some kind of abuse as the reason for her behaviour); and instead focus solely on ‘fixing’ her as a woman and as an adult member of society.

Shiraha has some… interesting ideas about the Stone Age, specifically because scientists have suggested, rather, that ‘unproductive’ members of tribes were not abandoned, and that the sick were cared for. But I suppose it fits too nicely with his Nice Guys Finish Last mentality to believe the things he spouts.

Still, Keiko agrees with him (in a very roundabout way) that society is in some way ‘defective,’ and that their life choices should be no-one else’s business. Of course, the difference is that he wants only to shirk any and all responsibilities that he brought on himself, while repressive attitudes towards unmarried women — so painfully illustrated in Shiraha’s barrage of insults to Keiko’s own status and appearance — are put forth as a rather more understandable reason for wanting to escape.

Keiko is at once aware of both class and sexist prejudices (and very tired of them), but she does not openly challenge them because infinitely more important than her class or gender identity, to her, is her life as a convenience store worker. That is not just what she is, or what she does, it’s who she is.

She has no other ambition, and is carving out a place for herself in a space where she is told she should not be, as—

- store worker is only for students, job-hoppers, housewives, etc.; anyone either on their way to a career or not in need of one because they are married

- she is too old, and as a woman, should go and get married to be ‘normal’

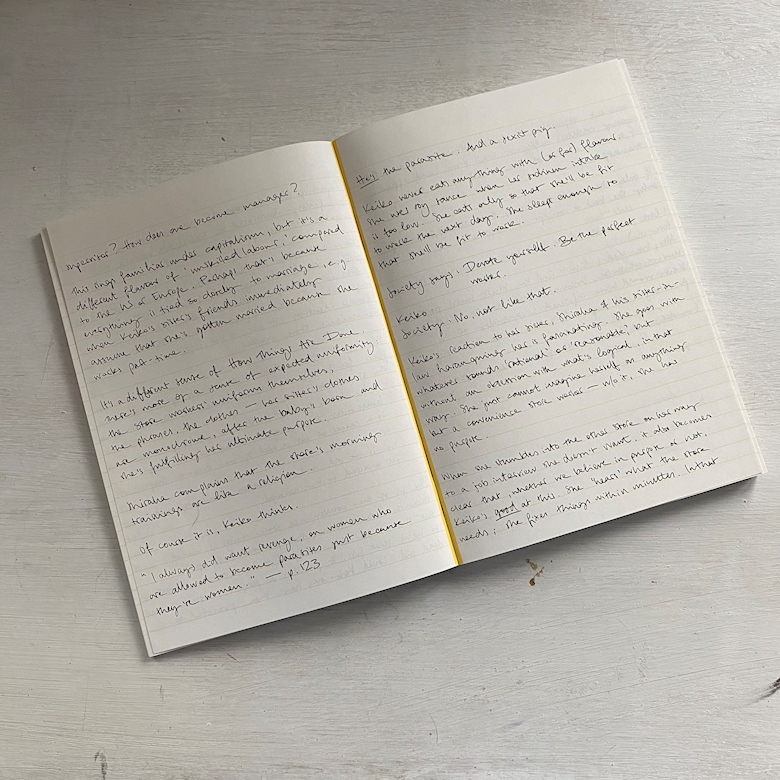

The job of the convenience store worker is needed because without them, things would fall apart (2020, anyone?), but there is no value assigned to it — no-one ought to want that job, because it is not a career. It provides no prospects, it’s a dead end to anyone but Keiko. Could Keiko ever have been promoted to supervisor, I wonder? How does one become manager?

This all rings familiar under capitalism, but because the story is a Japanese one, it’s a different flavour of ‘unskilled labour’ compared to the US or Europe, the main frames of reference for this debate and global public discourse at this point. It seems that that’s because everything is tied so closely to marriage, for example when Keiko’s sister’s friends immediately assume that she’s gotten married because she only works part-time. That just makes sense, they say.

It’s a unique sense of How Things Are Done, there’s more of a sense of expected uniformity: the store workers’ uniforms themselves, the phrases, the clothes outside of the store, too — her sister’s clothes turn monochrome, Keiko observes, after the baby’s born and she’s fulfilling her ultimate purpose to society. (Declining birth rates are brought up more than once.)

Shiraha complains that the store’s morning trainings are like a religion.

“Of course it is, Keiko thinks.”

Shiraha is just… such a dick. I was so glad when he seemed to have left for good — but then, why introduce such a nuisance of a character (such a nuisance of a man) and then just let him go? Of course, in a somewhat nutty novel like this, anything could happen… and it does!

Another gem from Shiraha:

“I always wanted revenge, on women who are allowed to become parasites just because they’re women.”

— p. 123

Again, the same vicious cycle: women are pushed into a certain role, some fight, others resign themselves, some make the most of it, and whichever they do, it is used against the whole gender. What Shiraha means is women spending their husbands’ money because there’s nothing else they’re allowed to do. And Shiraha thinks that they have it good — and equally he denigrates women who have their own careers and work successfully. Any guesses? Yes, because they would never go out with him.

Keiko never eats anything with (or for) flavour. She uses soy sauce only when her sodium intake is too low. She eats only so that she’ll be fit to work the next day. She sleeps enough so that she’ll be physically fit for work. It’s a phrase oft-repeated.

Society says: Devote yourself. Be the perfect worker.

Keiko:

Society: No, not like that.

Keiko’s reaction to her sister, Shiraha and his sister-in-law haranguing her is fascinating. She goes with whatever sounds ‘rational’ or ‘reasonable,’ but without an obsession with what’s ‘logical,’ in that way. She just cannot imagine herself as anything but a convenience store worker — without it, she has no purpose.

When she stumbles into the other store on her way to a job interview she doesn’t want, it also becomes clear that, whether we believe in purpose or not, Keiko’s good at this. She’s internalised the original store’s manual and goals, right down to her marrow. She ‘hears’ what the store needs; she fixes things within minutes. In that moment, especially with her trouser suit and the young cashiers instantly believing that she’s been sent down from head office, it becomes clear that she ought to be store manager.

If only she could conceive of that ambition — if only she had a concept of happiness. But perhaps, going on as she has been, she will be happy.

I loved this book.I wonder what my friend, who’s read far more Japanese literature than I have, will make of it when she reads it.